Coreference Resolution for Literary Texts

05 Dec 2021 | Coreference Resolution Neural Network English Literature Computational HumanitiesThe Task

The coreference resolution task is a long-standing clustering task in Natural Language Processing (NLP) that links mentions that refer to the same entities together. A mention is a noun or a noun phrase and normally falls into categories such as a person, a location, or an organization, etc. Given this definition, the coreference resolution task is often closely related to the Named Entity Recognition (NER) task, where it identifies all named entities (such as person, location, organization, date, etc.). And indeed, NER is always incorporated in coreference resolution models or inference algorithms.

For example, consider the following sentence:

“(Harry Potter) is the (boy-who-lived), and (he) made {Voldemort} lose {his} power when (he) was a baby.” As humans, we can easily perceive that the mentions in parenthesis are referring to Harry, and in curly brackets are the ones referring to Voldemort. However, more complex sentence structures will give rise to subtle challenges for this task.

Coreference resolution has lots of applications, and is often an important foundational task in many NLP tasks, such as question answering, text summarization, reading comprehension, and in interdisciplinary areas such as computational social sciences and humanities, which we’ll elaborate on in this post.

Challenges for the Literary domain

There are several challenges for the literary domain, some notable ones as follows:

-

Lengthy sentences: according to [Bamman et al.,2020], literary texts in the Litbank dataset, a representative selection of 100 works from classic English literary texts across 18th to 20th century, are four times longer than the OntoNotes dataset for traditional named entity recognition tasks. The length of the sentence poses a significant challenge for the coreference models as they tend to have limited maximal distances for preceding and subsequent spans to make inferences on.

-

Nested mentions: unlike straightforward news texts and day-to-day English usage, literary texts often contain ambiguous nested structures in their figurative language usages. For example, “the smart and wise Hobbit Frodo” has two layers of mentions: the entire phrase, or just “Frodo”, the proper name. Given this challenge, coreference resolution models for the English literature domain often needs to be trained on either the longest or shortest spans of mentions.

-

Ambiguity: unlike newswires or reports, literary entities can change over the course of a novel. For instance, as Bamman et al. mentions, is the seven-year-old Pip at the beginning of Dicken’s Great Expectations the same identity as the thiry-year-old Pip in the end? Such questions are philosophical and computer programs cannot answer in full. Most coreference systems treat the entities as static throughout a piece of text for simplicity.

Evaluation metrics

Having briefly elaborated on the task itself as well as specific domain challenges, let us turn to the evaluation metrics before diving into the specific model architectures. To evaluate the effectiveness of a coreference resolution model, the research community has developed several metrics employed in the well-known CONLL shared task:

-

B-CUBED. This metric takes the weighted sum of the precision or recall for each mention, e.g. $ Recall = \sum_{r \in R} w_r \cdot \sum_{t \in T} \frac{|t \cap r|^2}{|t|} $. $R$ is the predicted result set of entity clusters, $T$ is the true set of entity clusters, $w_r$ is the weight for entity $r$, and the right-most factor is the number of true positives divided by the number of all positives [Moosavi et al., 2016].

-

MUC. If we consider a coreferent cluster as a set of linked mentions, the MUC metric measures the minimum number of link modifications needed to make $R$ the same as $T$. The partition function measures the number of clusters in the set of predicted clusters $R$ that intersect with the given true cluster \(t\).

-

CEAF. This metric first maps predicted result entity clusters $r \in R$ to true entity clusters $t \in T$ via a similarity measure denoted $\phi(T, R)$. We then use the mapped true cluster $m(r)$ with maximum similarity to $r$ to compute the precision or recall.

Coreference Models

Popular Approaches at a Glance

As coreference resolution is a long-standing traditional task, there has been a surge of rule-based, linguistic-driven, and neural-network-based approaches. [Lee et al., 2017] has summarized the popular model approaches as follows:

- Mention-pair classifiers

Being the most intuitive yet inefficient model type, mention-pair classifiers iterate over all possible pairs of mentions (where a `mention’ is defined as a reference to an entity) and train a binary classifier on each pair to predict whether or not the mentions in that pair are coreferent. Then define some thresholding criterion to turn these yes-no coreference pairs into a cluster of mentions for each entity.

- Entity-level models

Entity-level models, also called cluster-based models, incorporate features defined over clusters of entities as opposed to just mention pairs when making decisions regarding coreference scores. In [Clark and Manning, 2016], the authors proposed a neural network approach with dense vector representations over pairs of coreference clusters for model training.

- Mention-ranking models

The mention-pair method only indirectly solves the coreference resolution task. Note that we want clusters for each entity, not coreferent pairs, and it is unclear what is the best way to merge these pairs into clusters. Furthermore, the mention-pair technique allows for incompatible mentions in the same cluster: a female entity could be coreferent with “he” in one pair and coreferent with “she” in another pair, so the gender of the cluster would be ambiguous. The mention-ranking approach helps prevent this problem by ranking the possible antecedents and choosing just one antecedent for a given mention.

End-to-end Neural Coreference Resolution

[Lee et al., 2017] has proposed the first end-to-end neural coreference resolution system that becomes the foundation for many subsequent neural-network based approaches for this task in the literary domain. Then, what does their architecture look like?

The Key Idea

The approache considers all possible spans within a given document as potential mentions, and learns distributions over possible antecedents for each. The model computes contextualized span embeddings with the attention mechanism, and maximizes the marginal likelihood of gold antecedent spans from coreference clusters.

The Input

The input for the model contains a document, D, containing T words, with optional metadata such as speakers or genre information.

The Model

[Lee et al., 2017] utilizes LSTM and attention mechanisms for their architecture, and defined pair-wise coreference scores to apply in their span representations.

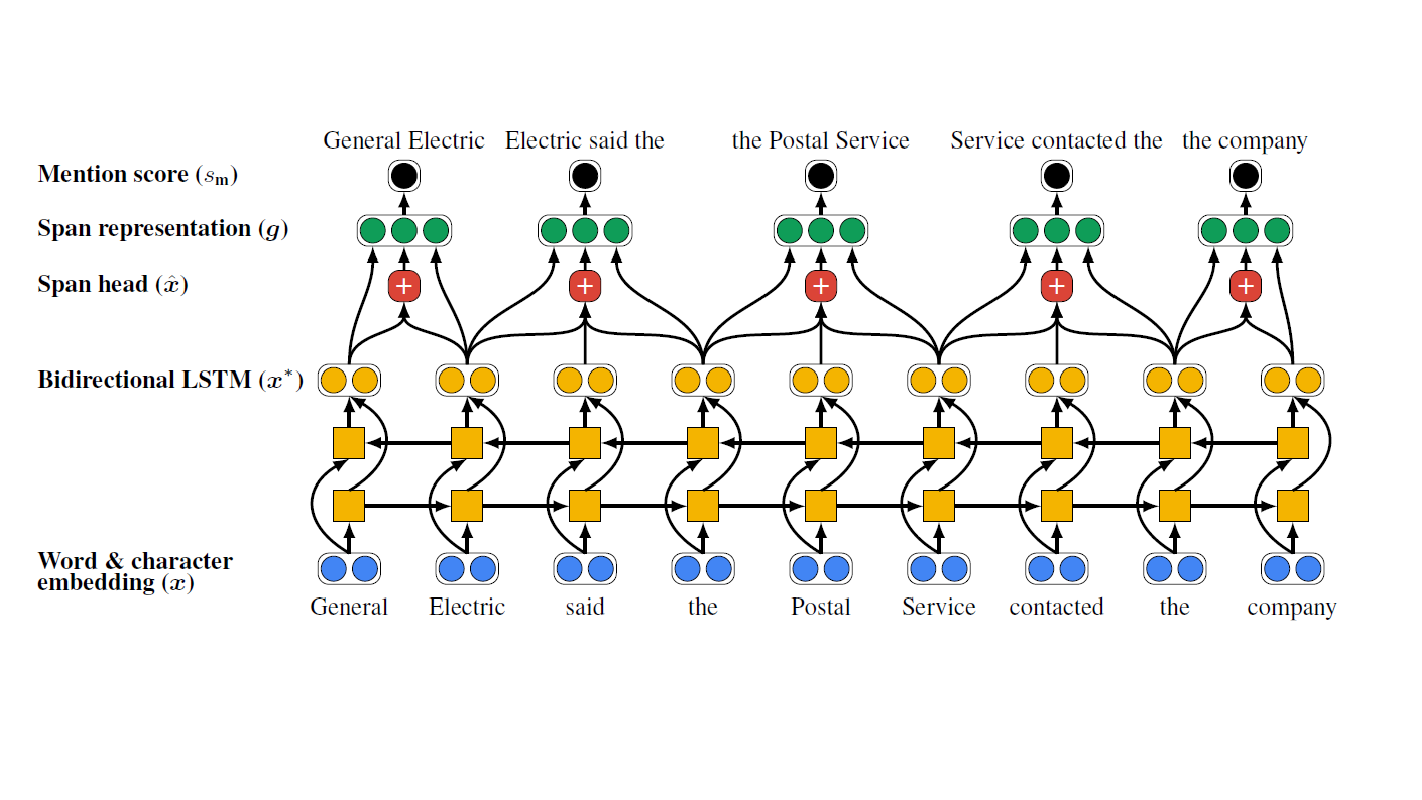

Input to Span Representation

-

The first step of the end-to-end pipeline takes in the document input (as simple as a sentence), tokenize and calculate the word and character embedding (x), fixed pretrained word embeddings from 300-dimensonal GloVe embeddings, and 1-dimensional convolution neural networks (CNN) over characters.

-

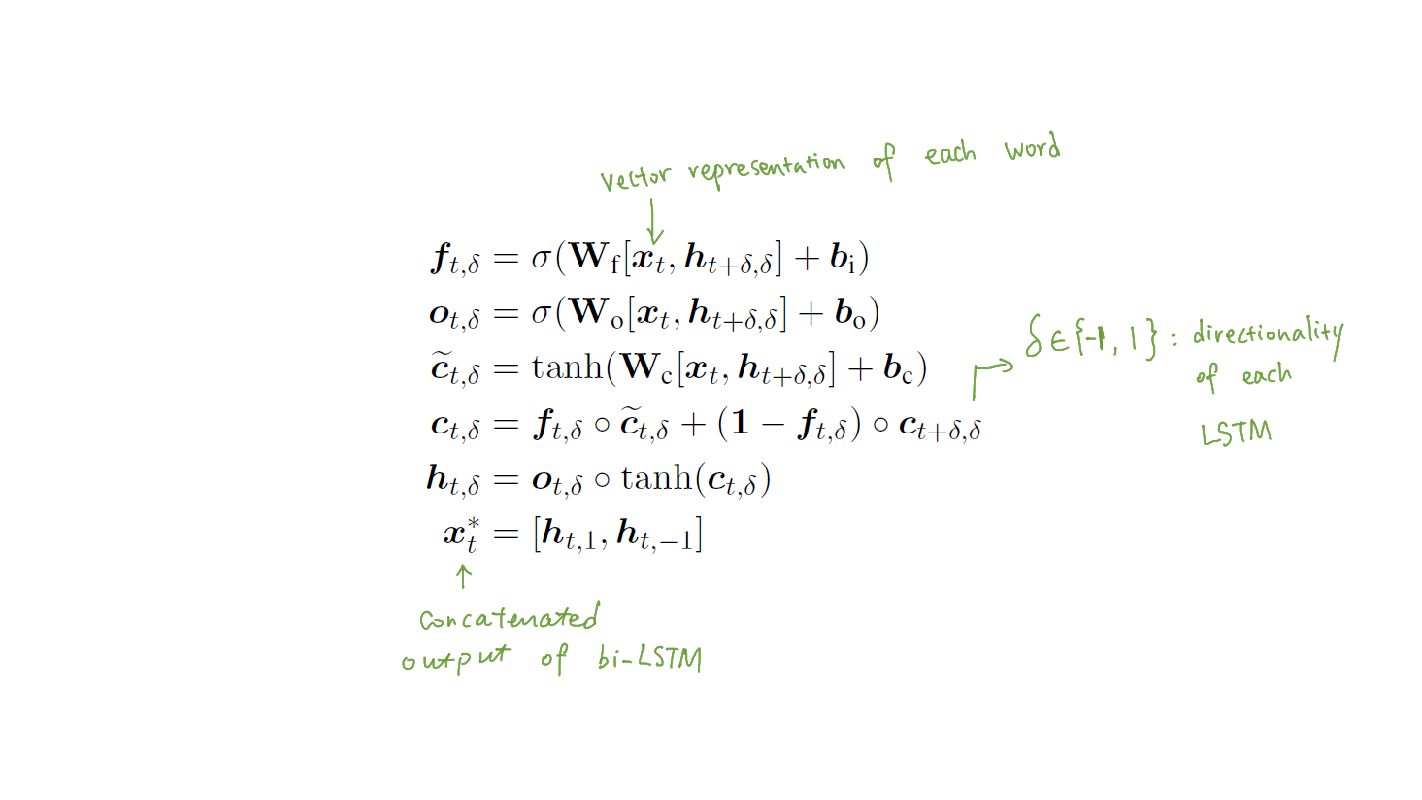

The word embeddings then are feeded as inputs into the Bidirectional LSTM network (x*), where it encodes each word in its context, as the surrounding context for each mention span plays an integral role on the scoring of the coreference pairs.

As we can observe from the equations above, x*t is the concatenated output of the bidirectional LSTM.

It is interesting to note that Lee et al. only uses independent LSTMs for every sentence and decides that cross-sentence context is not helpful, this is not the case for literary texts as the mentions can span across chapters.

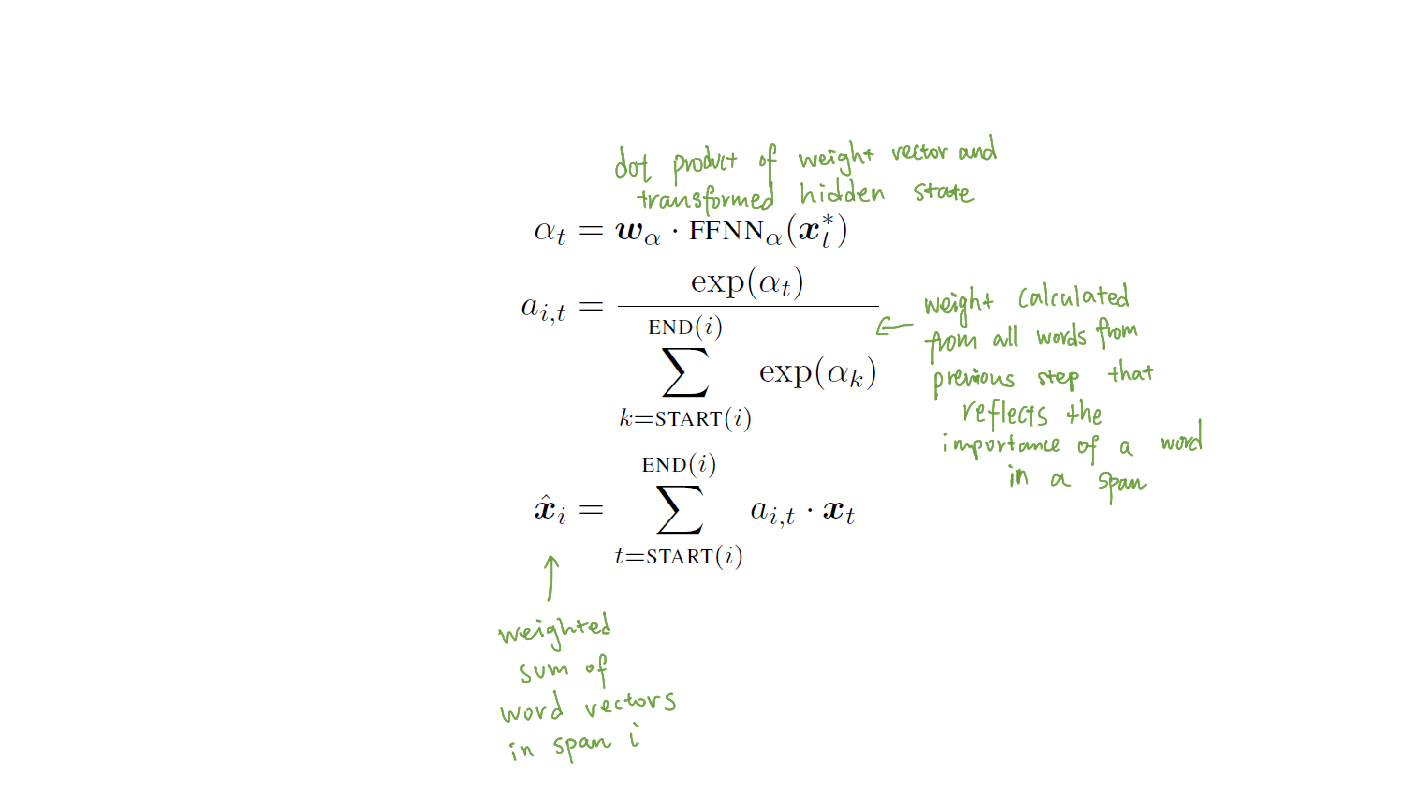

- The Bidirectional LSTM outputs then gets passed to the next layer of the network to calculate the span head \(\hat{x}\), where it is a weighted sum of word vectors in a given span. Attention mechanism is applied using this step over words within each span.

- The final span representation is then calculated as the accumulation of all the above information with:

_191.png)

Coreference Scoring Calculation

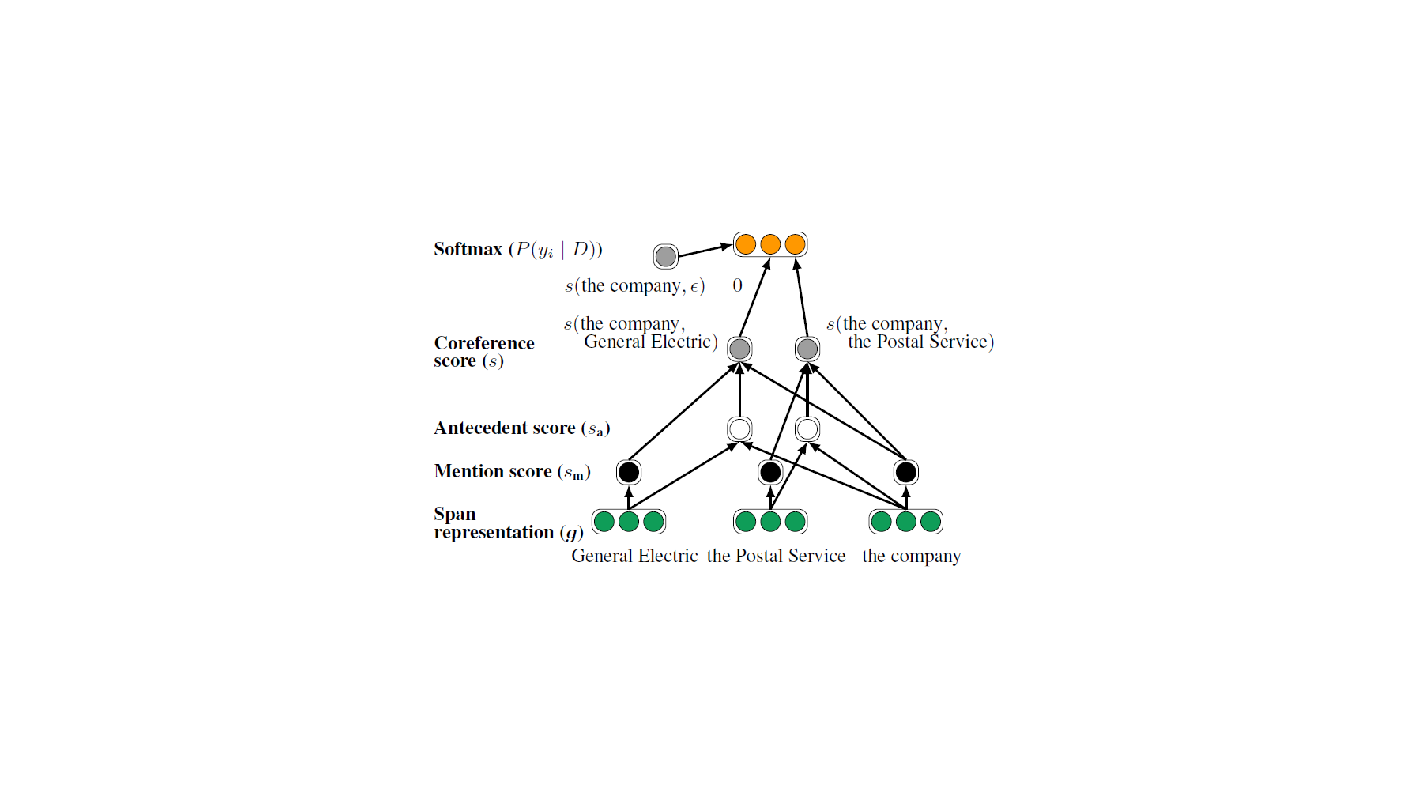

- Once we have the span representation calculated from the first step, we then move on to the coreference scoring calculation step to obtain the final coreference score for a pair of spans.

The architecture is as follows:

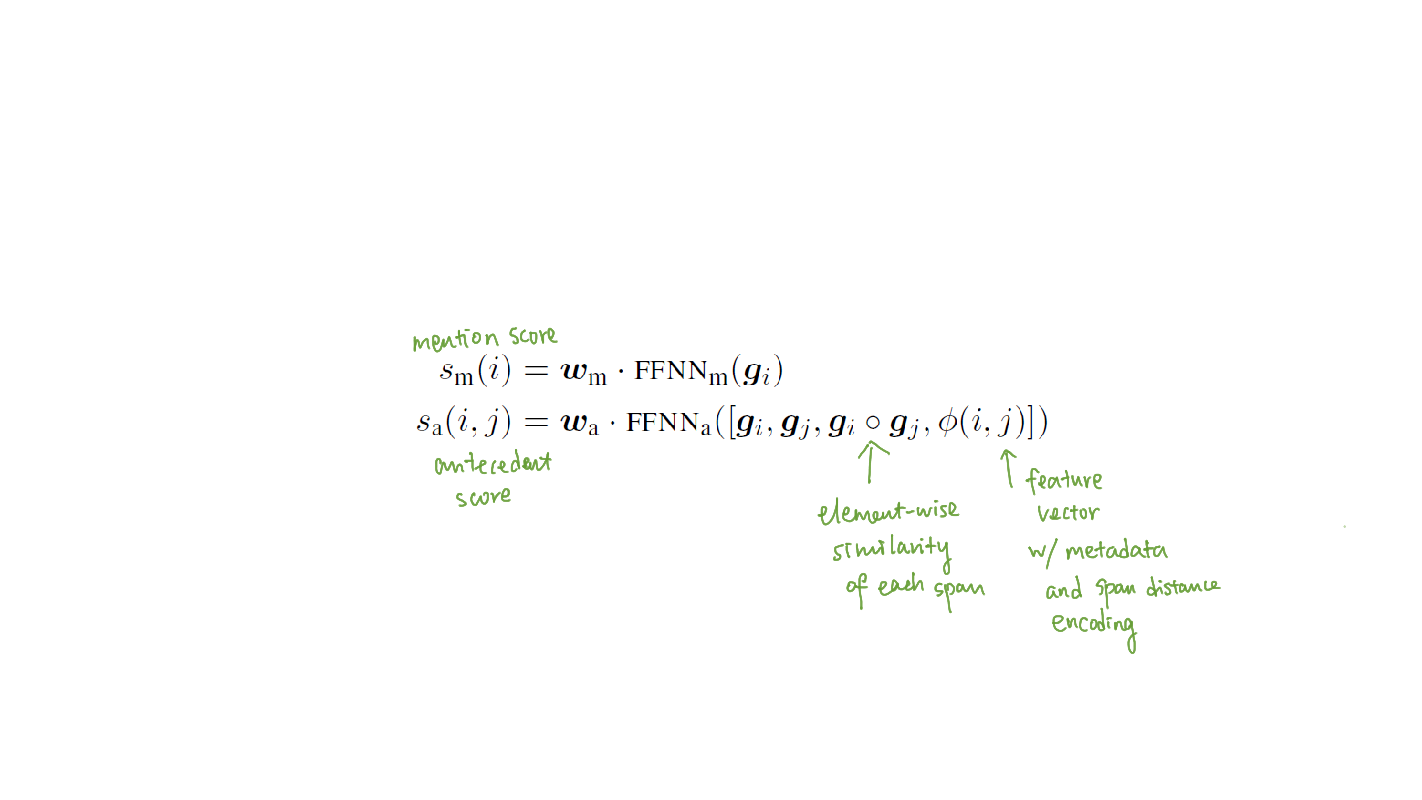

Recall from the last step that each possible span i in the document will have a corresponding vector representation $g(i)$. Given the span representations, the scoring functions are then calculated via feed-forward neural networks:

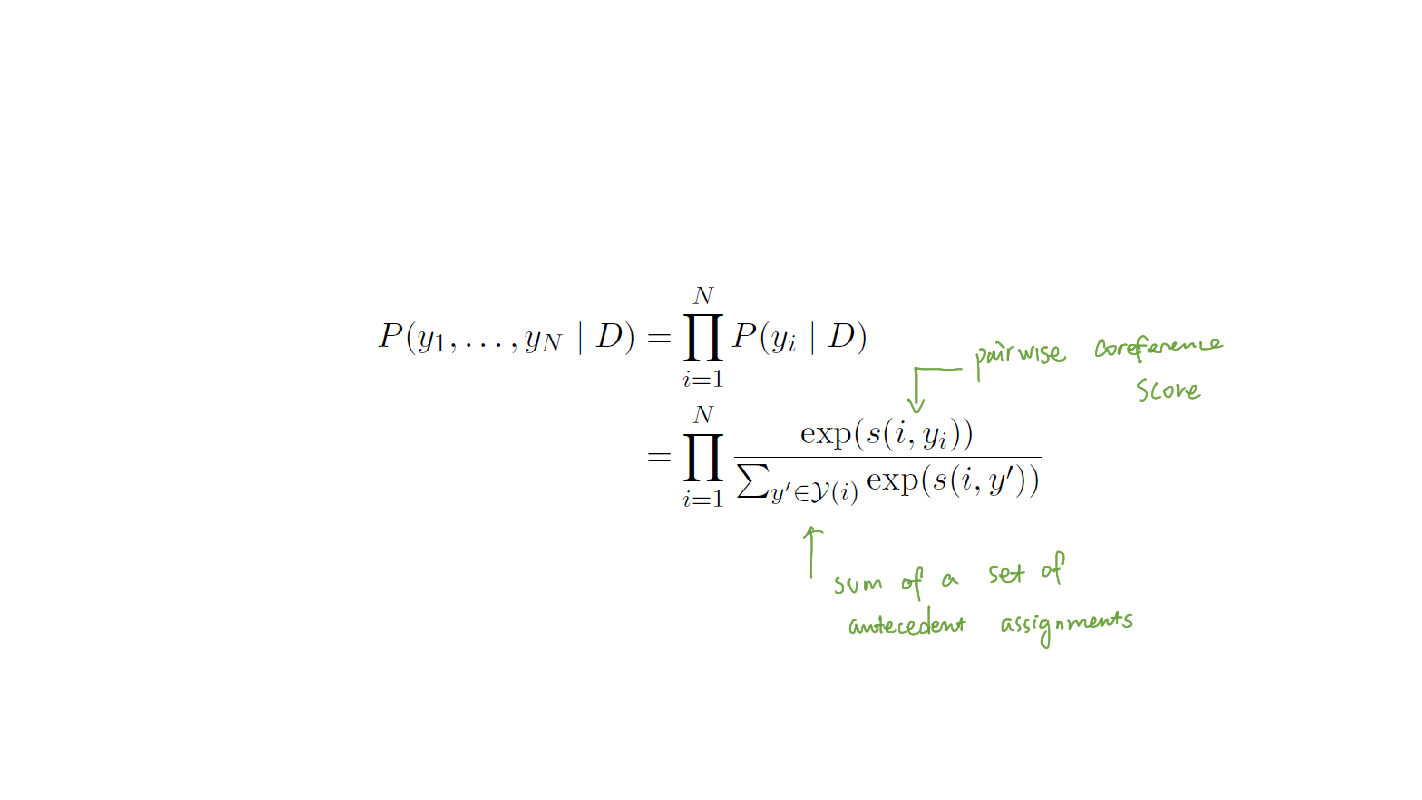

- With the coreference score (s) being calculated, we are finally able to learn the conditional probability distribution with the final softmax layer to represent the most likely configuration that produces the correct clustering.

The equation is as follows:

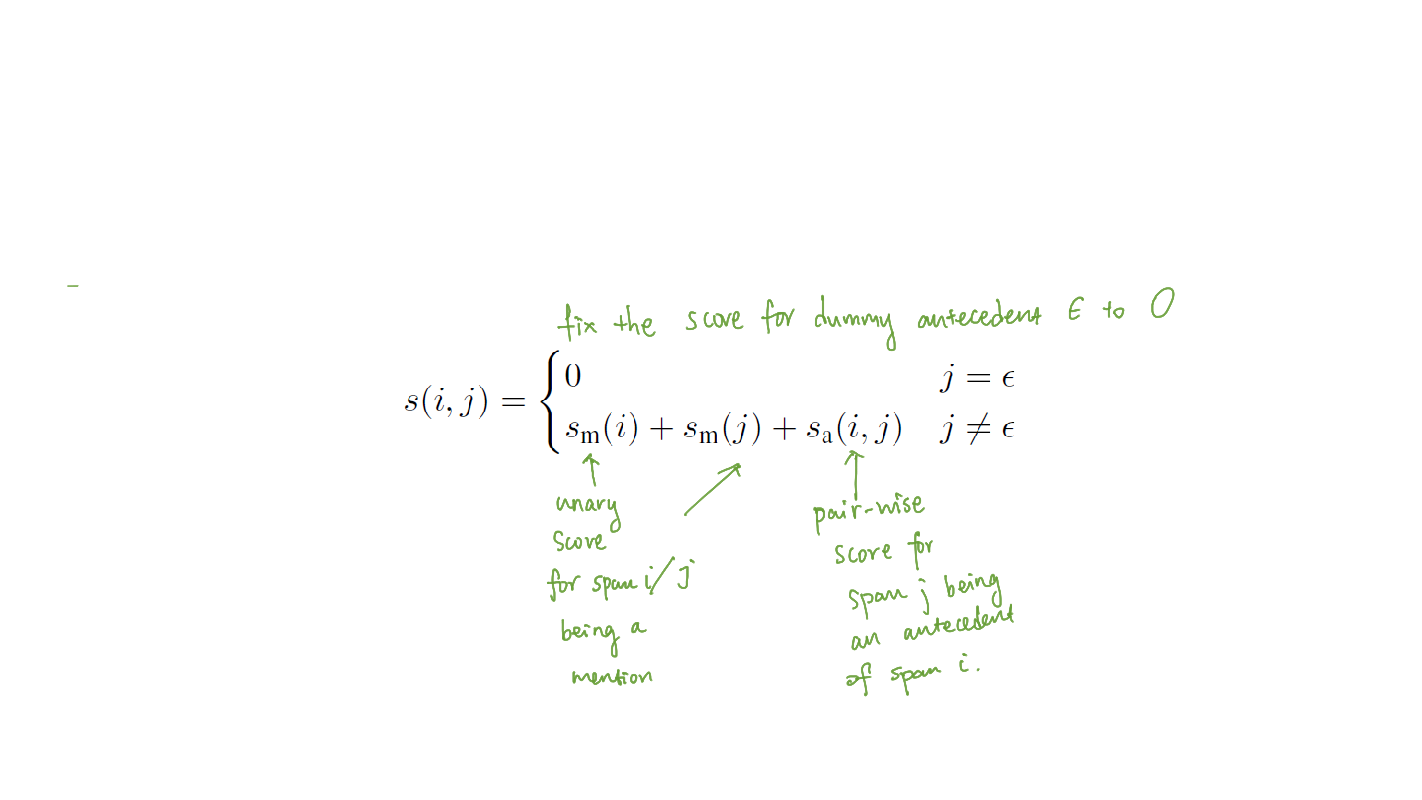

$s(i,j)$ is the pairwise score for a coreference link between span i and span j in document D. Lee et al. define it as follows:

The $\epsilon$ represents the dummy antecedent, where span j is either not an entity mention, or it is an entity mention but it is not coreferent with any previous span. By setting the coreference score to 0, the model is able to aggressively prune away the pairs less likely to belong in the same cluster to save computational costs.

Challenges

(1) As mentioned in the paper, the biggest challenge of the model is the computational size, with the full model reaching $O(T^4)$ with document length T. To address this challenge, the authors proposes an aggressive pruning approach where they greedily prune potential spans with the following constraints: They only consider spans up to L words for unary mention scores; further, they only keep the top $\lambda*T$ spans with the highest mention scores and consider only up to K antecedents for each.

(2) From a qualitative analysis, we can observe that the usage of word embeddings for word similarity makes the model prone to predicting false positive links with related/similar words. Consider the following example listed in the paper: “(The flight attendants) have until 6:00 today to ratify labor concessions. (The pilots’) union and ground crew did so yesterday.” The model mistakenly identifies “the flight attendants” and “the pilots’” as coreferent, possibly due to the shared contextual embeddings they have.

(3) We can also observe the texts for experiments are relatively simple without too complex syntactic structures or figurative languages. While this is sufficient for most daily text sources, literature does requires more finetuning and domain-specific adaptations.

LitBank Coreference Pipeline

As mentioned above, the Litbank dataset features selections from 100 English-language novels between the 18-20 century. The Litbank literary coreference dataset [Bamman et al., 2020] contains 29,103 mentions in 210,532 tokens from 100 fictions.

Bamman et al. also trained a coreference resolution system specifically for the literary domain. The model is largely built upon Lee et al.’s pipeline with the following differences:

- BERT contextual representations instead of static GloVe word vectors and a subword character CNN

- Train and predict conditioning on mention boundaries

- No author/genre information

- Only antecedents within 20 mentions for pronouns and 300 mentions for proper noun phrases and common noun phrases.

Bamman et al.’s architecture, similar to Lee et al.’s, can be summarized in the following two steps:

-

Mention Representations Bamman et al. computed representations for each mention span by passing BERT contextual representations to a bidirectional LSTM, then through an attention network, then finally through various embeddings of span width and location within a quotation.

-

Mention Ranking Each mention span representation is passed through a linear network, concatenated with representations of previous spans (which correspond to all the possible candidate antecedents), and finally concatenated with yet more embeddings representing distance and nested mentions. Then, a score is computed for each candidate antecedent.

FanfictionNLP Character Coreference Pipeline

The fanfictionNLP pipeline [Yoder et al. 2021] is a text processing pipeline designed for fanfictions. It contains the following modules: character coreference, assertion extraction, quote attribution. For the purpose of our post, we’re only focus on the first module and the underlying coreference resolution model within it.

Similar to Bamman et al, FanfictionNLP pipeline also applies the Lee et al.’s architecture with the following modifications:

-

SpanBERT-based embeddings for contextual mention representations. SpanBERT [Joshi et al., 2020] is a variation of the BERT models and also the current state-of-the-art for the OntoNotes and CoNLL benchmarks, outperforms BERT on coreference resolution tasks by masking spans of tokens instead of individual ones.

-

Fine-tuning on Litbank dataset in addition to the original OntoNotes dataset that SpanBERT is trained on.

Domain-specific Challenges and Future Work

For a more intuitive understanding of the effectiveness of coreference resolution models on literary texts, let us look at some actual examples that I have based on the FanfictionNLP architecture with a custom entity recognition model:

“[The family of Dashwood had long been settled in Sussex]…{The late owner of this estate} was a , had [[a constant companion]] and ((housekeeper inhis sister)).” (Austen.Sense and Sensibility)

The different kinds of brackets indicate specific groups of mentions. Besides the few notable cases where the entities are not being correctly identified, such as the first entity being too excessive to include the modifiers of “the family of Dashwood”, the coreference model also makes a few mistakes on the linkage between mentions. In this example, it does not recognize that ‘the late owner of this estate’ and ‘a singleman’ are the same entity. This is a common type ofmistake and reflects the ambiguity in literary texts where characters are often referred to by epithetsor descriptions rather than names. Austen’s long sentences, ample use of descriptors rather than names, and frequent nested mentions make it difficult to resolve entities.

A final problem is that very prominent entities representing main characters, like ‘Harry’ or ‘Mr. Dashwood,’ tend to appear in multiple clusters (see the very noisy Figure 6), because the coreference model has trouble recognizing coreferent links that are distant from each other (i.e. in different paragraphs). Hence, to fully resolve literary mentions, we might need multiple models along the pipeline: one coreference model for identifying and linking entities, and another model for merging them. We might also want to consider ensembling models trained on spans of different lengths to make a collective decision regarding nested mentions.

Besides the specific challenges of the model itself as demonstrated by the example, the other challenge of developing neural-network based coreference models is the lack of training data, as hand-labeled gold standard data are extremely expensive to obtain with a high requirement of expertise required. Therefore, another future area of research might be also the generations of synthetic training data, which might also potentially help enhance model developments.